For years my homelab has been a rotating cast of hardware — Xeons, Core i7s, SFF boxes — each iteration teaching me something new. My latest build, a Lenovo P3 Ultra with an i9-14900T, introduced a new wrinkle: Intel's P- and E-core architecture.

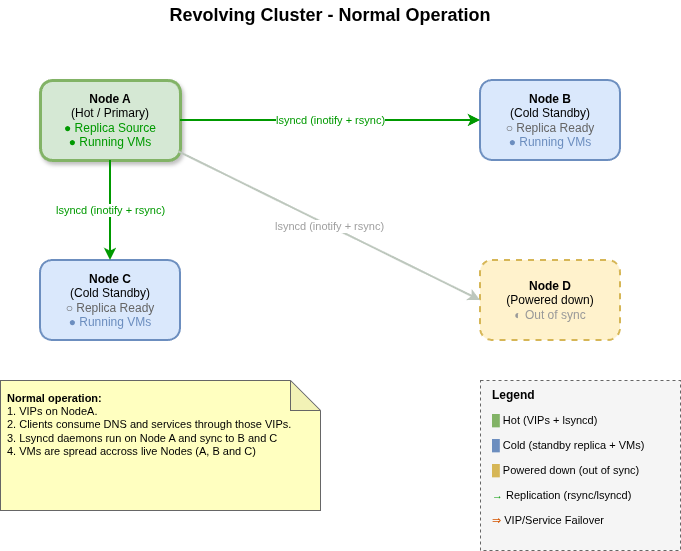

While experimenting with it, I ended up building a cluster that looks different from the typical enterprise and homelab high-availability setups you see online. I call it the Revolving Cluster.

It's not HA in the enterprise sense, but it gives me instant failover for critical services, fast recovery for VMs, and simplicity — three things I value more in a homelab than strict uptime for everything.

The Philosophy: Revolving, Mostly Redundant and Thoroughly Replicated

Most homelabbers chase HA clusters (Proxmox, Ceph, vSAN, etc.). Those are powerful but bring real complexity: quorum management, shared storage, fencing, migration coordination.

I wanted something with less moving parts and without shared storage. The Revolving Cluster is:

- Shared-nothing: each node is fully self-contained with its own storage.

- Replicated: critical files sync in real-time; VMs exist in multiple places but only run on one node.

- VIP-driven failover: critical services (DNS, files) fail over instantly via VIPs; VMs can be started cold elsewhere.

Think of it as two-tier HA: instant for critical services, manual for VMs.

Cluster Topology

Here's the basic layout:

- Node A, B: full-size servers with massive storage.

- Node C, D: compact workstations, smaller but capable.

- At any time, only one node is "master" (holding the VIPs).

- Replication flows from master → all other live nodes.

Cluster Hardware

Here's what each node brings to the cluster:

| Node | CPU | RAM | Boot Storage | Data Storage | Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Dell T640) | 2× Xeon 8269CY (52 cores) |

1024 GB ECC | 2 TB (EVO 870) |

15 TB + 15 TB + 32 TB (Micron 9400) |

4×10G (X710) 2×25G (XXV710) |

| B (Dell T640) | 2× Xeon 8280M (56 cores) |

1024 GB ECC | 2 TB (EVO 870) |

15 TB + 15 TB + 32 TB (Micron 9400) |

4×10G (X710) 2×25G (XXV710) |

| C (Lenovo P3 Ultra) | 8P + 8E cores (i9-14900T) |

192 GB ECC | 4 TB (EVO 990) |

8 TB + 32 TB (Micron 9400) |

1G + 2.5G 2×25G (XXV710) |

| D (Lenovo P3 Ultra) | 8P + 8E cores (i9-14900T) |

192 GB ECC | 4 TB (EVO 990) |

8 TB + 32 TB (Micron 9400) |

1G + 2.5G 2×25G (XXV710) |

The T640s are the heavy lifters — they can run the full VM workload including lab environments. The P3 Ultras are compact (3.9L) but still capable of running all critical infrastructure VMs if the T640s go down.

Power note: The T640s idle at around 220W each, so most of the time only one of them is powered on. The second T640 stays off until needed for extra capacity or maintenance failover. The P3 Ultras, idling at a fraction of that, run continuously.

Two Tiers of Service

Not everything in the cluster has the same recovery requirements. I run two tiers with very different RTO/RPO characteristics:

Tier 1: Critical Infrastructure (Sub-Second RTO and RPO)

These services are what the rest of my homelab and home network depend on. All clients use the cluster's VIPs for DNS, file shares, and home directories.

Key design point: stateless services run on all nodes simultaneously, not just the active one:

- DNS (bind/named): Every node runs bind with a full copy of all zones.

- File sharing (NFS and CIFS): Every node exports the same paths, serving from its local replica.

- Wireguard: Every node runs the VPN endpoint.

The VIPs simply direct client traffic to one of these identical services. When a node fails, the VIPs move to another node — which is already running the same services with the same data. Clients see a brief hiccup (sub-second), then continue as if nothing happened.

- RTO (Recovery Time): sub-second — VIPs move instantly to a node that's already serving.

- RPO (Data Loss): sub-second — lsyncd replication is continuous.

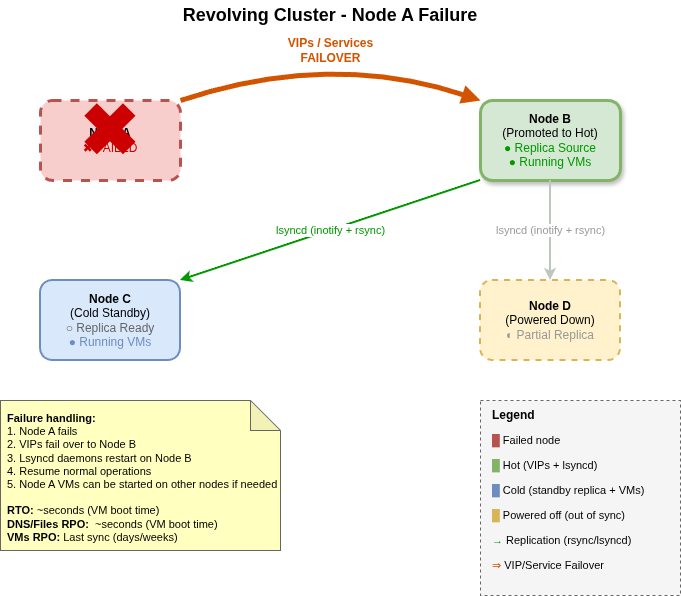

Tier 2: Virtual Machines (Fast RTO, Longer RPO)

VMs are a different story. They're large, change frequently, and continuous replication would be expensive. Every node in the cluster has a copy of all important VMs — the copy might be a few days old, or newer depending on the last sync. VMs can run on any node, but each VM runs on only one node at a time to avoid split-brain scenarios.

- RTO (Recovery Time): seconds — just the time to boot a VM from the local copy on a surviving node.

- RPO (Data Loss): days or weeks — VM replication is snapshot-based, not continuous. The replica might be from the last scheduled sync, so recent changes inside the VM may be lost.

Recovery is manual: if a node fails, I decide which VMs need to be restarted on surviving nodes, and I start them from the local replica — even if it's a few days old. This deliberate manual step prevents two nodes from running the same VM simultaneously.

Design Principle: Separate Compute from Critical Data

The key insight here is that nothing inside a VM should require sub-second replication. If it does, I move that data out of the VM and onto NFS or CIFS — where it gets sub-second replication via lsyncd automatically.

This separation of concerns means:

- VMs are just compute — they can be restarted from an older replica without losing critical data.

- Critical data lives on the cluster's shared storage — accessed via NFS/CIFS, replicated in real-time.

This two-tier approach gives me the best of both worlds: instant failover with no data loss for critical data, and cost-effective cold standby for VM compute where I accept some staleness in exchange for simplicity.

Hardware Design Principles

Building a shared-nothing cluster with full replicas requires specific hardware considerations:

Storage: Every Node Holds Everything

Each node must have enough storage to hold a complete copy of everything important. The T640s can hold the full workload; the P3 Ultras hold all critical VMs but not the lab environments.

Network: Multiple High-Speed Links

Multiple 10G/25G links per node enable:

- Parallel replication streams for faster sync

- Redundant paths if a link or switch fails

- Separation of replication traffic from client traffic

Compute: Sized for Worst-Case Failover

Each node must have enough CPU and RAM to run all critical VMs, even if every other node fails. Critical VMs include:

- Active Directory (Samba4-based domain controllers)

- GitLab

- PKI / Certificate Authority

- IDM / Identity Management

- Container registries

Only the T640s can also run the lab VMs (OpenShift clusters, test environments), but any node can run the critical infrastructure.

Replication Strategy

Replication is the glue that makes the Revolving Cluster work. I use two different tools depending on the workload:

Real-Time Replication: lsyncd

For critical files (home directories, shared files, DNS zones), I use lsyncd — a daemon that watches for filesystem changes and triggers rsync immediately.

Important: lsyncd only runs on the master node (the one holding the VIPs). This is the sole location that determines replication direction — always from the master to all other live nodes.

- Latency: sub-second (changes propagate almost instantly).

- Direction: always from master (VIP holder) → all other live nodes.

- On failover: the new master starts lsyncd and becomes the replication source.

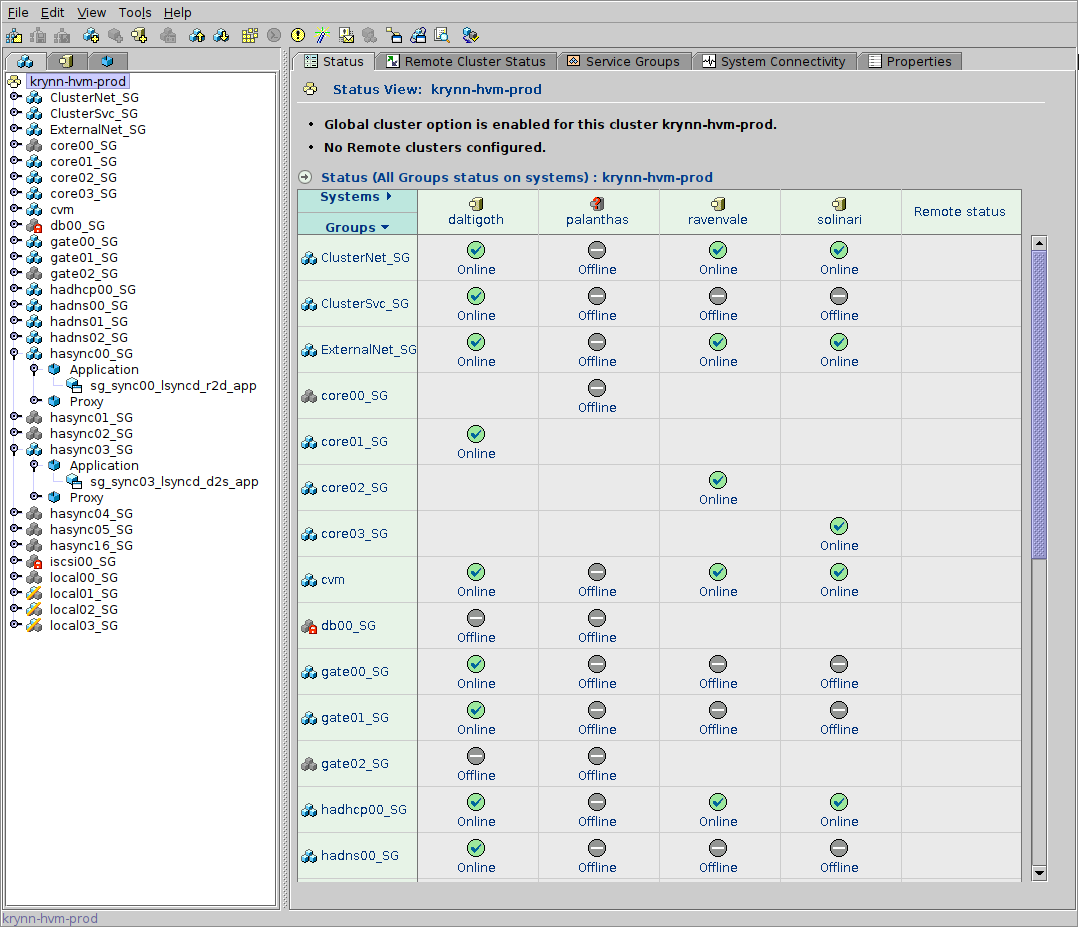

A Note on Service Group Scaling

Each node-to-node replication relationship requires a VCS service group. Since lsyncd replication is bidirectional (the active direction depends on which node holds the VIPs), you need one service group per unique node pair.

The formula is N × (N-1) / 2 — the classic "N choose 2" combinations formula (also known as the handshake problem):

- 2 nodes → 1 service group

- 3 nodes → 3 service groups

- 4 nodes → 6 service groups

This scales quadratically, so adding nodes increases complexity quickly.

In the VCS screenshot above, you can see this in action: the service

groups hasync00 through hasync05 represent

the 6 node-pair relationships needed for my 4-node cluster.

These service groups only come online when all of these conditions are true:

- Both nodes in the pair are live.

- One of them is holding the VIPs (i.e., is the master).

Otherwise, the service group stays down. For example, if Node A has the VIPs and Node D is down, only A↔B and A↔C will come up — the three service groups involving Node D remain offline.

Batch Replication: Custom Tooling for VMs

Rather than running rsync directly, I use a custom Python script (rsync_KVM_OS.py) that wraps rsync with VM-aware logic:

- Storage: qcow2 images (snapshotted before sync for consistency).

- Optimization: compression skipped for qcow2 to save CPU.

- Network: 10G/25G between nodes.

- Throughput: ~450 MB/s per file, with multiple streams running in parallel to saturate available links.

Tool Usage

# /shared/kvm0/scripts/rsync_KVM_OS.py --help usage: rsync_KVM_OS.py [-h] [-c] [-d] [-f] [-p] [-s] [-t] [-u] [--host HOST] [-V] [vm_list ...] Replicate KVM virtual machines to remote hypervisor positional arguments: vm_list List of VMs to replicate (default: all configured VMs) optional arguments: -h, --help show this help message and exit -c, --checksum Force checksumming -d, --debug Debug mode - show commands without executing -f, --force Overwrite even if files are more recent on destination -p, --poweroff Power off remote system when sync is done -s, --novxsnap Don't use vxfs snapshots even if supported -t, --test Don't copy, only perform a check test -u, --update Only update if newer files --host HOST Override destination host (default: auto-detect from script name) -V, --version Show version information and exit

The script handles VXFS snapshots automatically — it creates a snapshot before syncing, copies from the snapshot for consistency, then discards the snapshot when done.

Minimizing Downtime with Snapshots

VXFS snapshots are key to reducing VM downtime during replication. The workflow is:

- Shut down the VMs to ensure disk consistency.

- Launch the sync script, which takes a snapshot of the cold VMs.

- Restart the VMs immediately and continue working.

- The copy continues in the background from the snapshot.

This means the targeted VMs are only down for a few minutes — the time it takes for all VMs in the copy batch to shut down cleanly plus the snapshot creation — rather than the hours it would take to copy terabytes of data with VMs offline. VMs not in the batch keep running.

Scheduled Replication

For critical VMs (Active Directory, CA/PKI, IDM), I run scheduled weekly replications during a maintenance window. This ensures these VMs have reasonably fresh copies across all nodes without requiring continuous sync.

VIP Failover and Replication Direction

The magic that makes critical services highly available is the combination of VIPs and directional replication.

In my setup, VIP failover is managed by VCS (Veritas Cluster Server), but the same approach works with any HA software — Pacemaker, Keepalived, or even a simple scripted solution. The key is having something that monitors node health and moves VIPs automatically.

How It Works

- One node holds the VIPs — this is the "master" node. All client traffic for DNS, NFS, SMB, Wireguard flows through these VIPs to the master, though all nodes are running these services.

- Only the master runs lsyncd — replication always flows outward from the master to all other live nodes.

- On failure, VIPs move instantly — another node takes over the VIPs and becomes the new master. Since it was already running the stateless services, clients barely notice the switch.

- The new master starts lsyncd — replication direction changes automatically, now flowing from the new master to the remaining nodes.

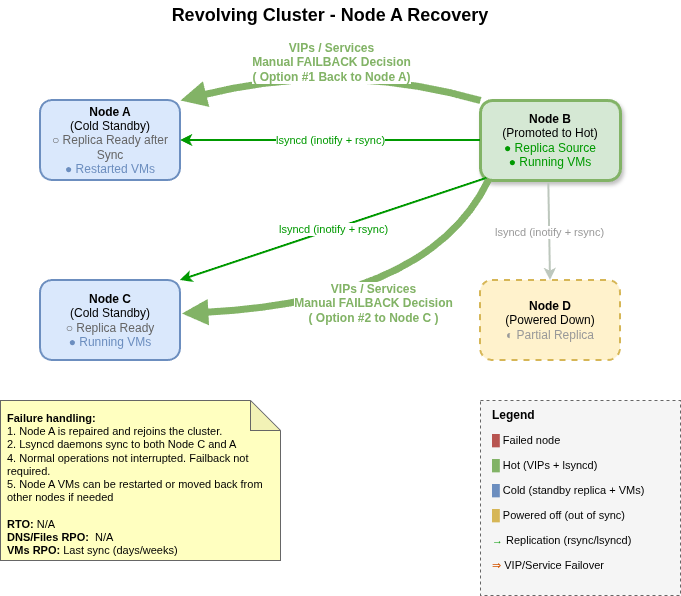

When a Failed Node Returns

This is where the design really shines. When a failed node comes back online:

- It rejoins the cluster as a standby node (not master) and starts its stateless services (DNS, NFS, CIFS, Wireguard).

- lsyncd on the current master detects the returning node and begins syncing any files that changed during the outage.

- Once caught up, the node is fully operational and ready to take over as master if another failure occurs.

There's no manual "resync" step — the returning node automatically receives everything it missed.

Startup Sequence

On boot, each node starts its stateless services (DNS, NFS, CIFS, Wireguard) immediately. Then:

- If it becomes master: it starts lsyncd and begins pushing file changes to all other live nodes.

- If it's a standby: it receives an initial sync from the current master's lsyncd, then continues receiving updates.

The initial sync completes quickly (seconds on a 10G network for incremental changes). After that, file replication runs continuously with sub-second latency. This is what enables the near-instant failover for critical services — every node is already serving, and their data is always current.

Why Not Ceph/Gluster/etc.?

Three reasons:

- Complexity. I don't want to manage quorum, fencing, and recovery logic.

- Overhead. Shared storage layers add latency and resource burn.

-

Transparency. With rsync, I can literally

lsmy replication state.

For a homelab, "good enough and understandable" beats "perfect but opaque."

Benefits of This Approach

- Flexible node count: Core workloads run regardless of how many nodes are in the cluster. With two or more nodes, I get fault tolerance. Even with a single node remaining, everything still runs — I just lose the safety net until another node rejoins.

- Repairs on your own schedule: This is a homelab, not a datacenter with SLAs. If a node fails, I don't need to rush to repair it — the remaining nodes keep everything running. Parts might take days or weeks to arrive, and I can wait for a weekend to do the repair. No 3 AM emergencies, no pressure.

- Transparent failover for critical services: DNS, files, and home directories fail over in sub-second time. Users and clients barely notice.

- Automatic replication direction: no manual intervention when nodes fail or return — replication adapts.

- Fast VM recovery: spin up a cold copy in seconds to minutes.

- Resiliency: every VM and file lives on multiple nodes.

- Simplicity: each node is standalone, no shared storage dependencies.

- Observability: replication is visible in logs and on disk — no hidden state.

The tradeoff — longer RPO for VMs — is one I'm willing to accept, especially since critical services have sub-second RPO.

Practical Notes

A few observations from running this setup:

Cost and Storage Efficiency

Let's be honest: this is not cost-effective in the traditional sense. With four nodes, I maintain four copies of all important VMs — plus another cold backup on the NAS. That's a lot of storage for redundancy.

Most of my large NVMe drives (the Micron 9400s) were sourced from eBay or purchased during exceptional one-time deals. Without those opportunities, this setup would be prohibitively expensive.

The Upside of Multiple Copies

Having multiple copies of VMs at different points in time has an unexpected benefit: easy recovery from corruption. If a VM gets corrupted (bad update, ransomware in a test, accidental deletion), I can restore from whichever replica is cleanest — whether that's yesterday's sync or last week's.

Custom Replication Tooling

I couldn't find an existing tool that fit my needs, so I wrote one from scratch in Python: rsync_KVM_OS.py. It handles:

- VXFS snapshots for consistent VM copies

- Parallel rsync of multiple VM files to saturate multiple 10G links

- Smart comparison to skip unchanged files

- Batch operations to minimize SSH overhead

Even with 10G networking and all these optimizations, copying a large 6TB VM still takes hours. There's no magic solution when the data is that big — you just have to wait.

Open Questions

- Replication cadence: should I schedule more frequent VM syncs to shrink RPO, or is the current cadence sufficient?

- Deduplication: would adding ZFS or btrfs save space across replicas, or add too much complexity?

- Automation: could VM failover be partially automated while still preventing split-brain?

Closing Thoughts

The Revolving Cluster isn't about enterprise HA. It's about homelab HA — with a twist: critical services get real HA (sub-second failover), while VMs get cost-effective cold standby.

- Critical services: DNS, files, homes — instant failover, clients don't notice.

- VMs: accept multi-day RPO gap in exchange for simplicity.

- Design: keep it understandable and observable.

The "revolving" nature comes from how replication direction follows the active node. Nodes can fail, return, and fail again — the cluster adapts automatically. The active node is always the source of truth, and standby nodes are always ready to take over.

It's a different way of thinking — instead of always-on everywhere, I aim for always-available services and always-recoverable VMs.

And in a homelab, that's often all you need.

If you're running a similar "shared-nothing" homelab, I'd love to hear how you balance RTO and RPO — and how you've solved the compute vs. critical data separation. Feel free to drop me a line.